I’m not a traditionally religious person. I’m too much of a skeptic to entrust whatever spirituality I possess to this or that set of metaphors. But I’m not arrogant enough for atheism. We’re land mammals who have evolved to survive under particular environmental conditions during a very narrow window of time on a satellite orbiting one of two hundred billion trillion stars, so it’s fair to say our minds and senses are a tad over-specialized to wrangle successfully with certain questions. Put bluntly, what do we know? Nowhere near enough to proclaim either for or against the existence of a godhead with any degree of certainty.

That said, I am fascinated by religions. Scripture is, across the board, a tremendous work of art; collectively, one of the best created.

I came across the Jonah story at a very young age. As a sucker for anything sea-related, the whale immediately hooked me. Who was this Jonah guy? What was it like inside that whale?

Only later did I learn that the story of Jonah (in its Judeo-Christian and Islamic versions) is an allegory for our own psychological development arc. Yes, there’s the hero’s quest, but there’s also the anti-hero’s attempt to run from it—that’s Jonah.

Jonah was ordered to travel to Nineveh, the Assyrian city near modern-day Mosul, Iraq. There, he was to warn the people that unless they mended their ungodly ways, their city would be destroyed. In the Biblical version, Jonah is a Jew who hates the Assyrians and doesn’t want to see them saved, and certainly doesn’t want to die trying to make it happen, so he decides to run away.

In the Islamic version, Jonah (Yunus) is a Muslim sent to Nineveh to warn the Ninevites to repent their idolatry and return to the one true God. He goes, delivers the message, and is roundly derided. Upset, frustrated, and a little bitter, he decides to abandon the city to its fate.

In both cases, he boards a ship at the port of Joppa (Tel Aviv) bound for Tarshish, in Modern Gibraltar, and so travels, like the sun, from East to West. That’s the arc of life, rising in the East of infancy and setting in the West of old age, and hopefully achieving a little wisdom in between. In other words, Jonah/Yunus ignores the godhead’s commands and, quite literally, gets on with his life.

But God said, “Not so fast, little prophet.” You don’t get to walk away from destiny, no matter how rough it is.

Jonah was thrown from the boat halfway through his journey (life) and was swallowed by Dag gadol (the great fish). He spent the next three days inside this fish, literally snatched out of life, suspended, like the Hanged Man in the Tarot. You might say those three days represent the first three stages of the alchemical process (calcination, dissolution, separation). Stewing in the fish’s juices (being slowly digested and divested of his worldly ‘skin’), he faced two choices: pray for death, or pray for deliverance. He chose the latter, so he was spat back out onto the shore and told to pull himself together (conjunction) and proceed with the remaining stages of the “great work” (fermentation, distillation, and coagulation).

We are all Jonah/Yunus, and we all spend our three days in the Great Fish (alembic). It happens to us individually, but also collectively, as a culture. It tends to happen cyclically.

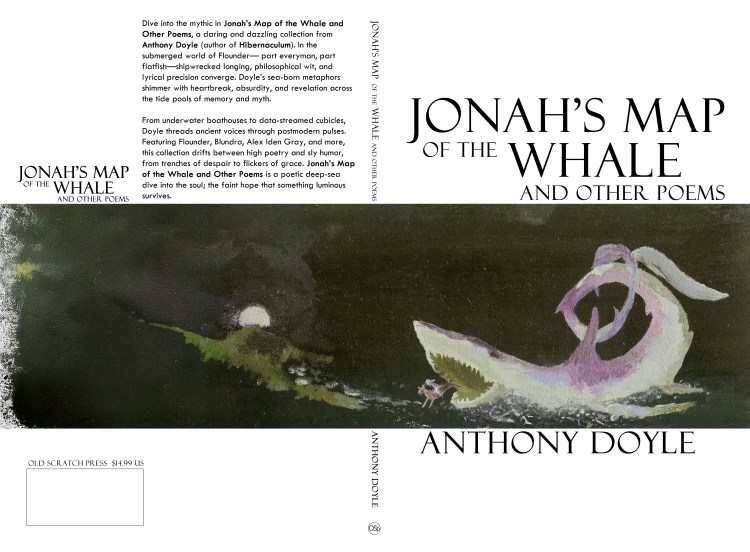

When I wrote Jonah’s Map of the Whale, a 1,200-line poem in sections, published in the book Jonah’s Map of the Whale and Other Poems (Old Scratch Press, 2025), that’s what I was trying to explore. Over fourteen sections, the poem backgrounds the life journey of a fictional character—a Wall Street money man named Alex Iden Gray—against the wider panorama of the turn of the 21st century. Alex Iden Gray (AIG, no coincidence) is partly named for a minor character in Shakespeare’s Henry VI, Part I. Alexander Iden, an esquire from Kent, is a man of his time, loyal to his king and true to the morals of his age (even when that involves beheading a troublemaker and taking his head to the king for belly rubs and treats). Alex Iden Gray is also true to the morals of his age—or lack thereof (hence the “Gray”)—and loyal to his “king”, read: money, capitalism, The American Way. He goes about his life against a backdrop of wars, financial crises, and technological developments, thriving within a system he knows, deep down, to be corrupt and damaging, but heck—he’s winning, so who cares? But throughout the poem, Alex finds himself being needled by potential epiphanies, which he resolutely ignores. Something is tugging him away from the mirror and towards the window, but he doesn’t want to look. Like Jonah/Yunas, he runs.

However, the godhead/universe/spirit has other plans. And this is where Alex meets his “great fish” in the form of a bull shark that rips his lower right leg off, leaving him in a coma that lasts precisely—you guessed it!—three days. During this coma, he is taken on an Ebenezer Scrooge-like revisitation of key events from his life (11 of the 14 sections).

When I wrote this poem, the devastation in Gaza had not yet happened. Russia had not invaded Ukraine. Trump 2.0 seemed all but unthinkable, and the AI genie had not been unleashed from its bottle. The world order appeared to be safely in place, as did its forums, courts, and treaties. ICE wasn’t rounding people up in the streets or shooting poets in their cars in The Land of the Free. The powerful weren’t adopting a smash-and-grab approach to other nations’ resources quite so flagrantly (they at least tried to disguise it, remember Colin Powell?), and the meek still believed they’d inherit the earth. Not today. A wave of bully politics has washed all the lines out of the sand, and the smaller powers, pulling on their invisibility cloaks, just sit there, hoping silence will be enough to keep them off their regional tyrant’s hitlist/wishlist.

The truth is, we’ve been so far up the asses of our own individualities and interiorities for the last decade, lost in a paradoxical pornography of self, posted daily on social media, that we failed to see this coming. We should have, but didn’t—or pretended not to. We were so preoccupied with tailoring and curating personal identities and categories-of-one, we lost whatever collective identity we might have had; so busy bickering about left and right that we failed to see what was straight in front of us: a great big fucking Nineveh rising out of the sands. And now we’re all Jonah. We know where the new Ninevehs are, and the three unwise kings who have carved up our map. We know how far they have strayed from international law, the fundamentals of democracy, and the basics of common decency. We know what our duty is as human beings: it’s to stand outside the city walls and deliver the warning of impending destruction. That’s not hyperbole: It’s highly unlikely our debilitated earth could withstand the kind of war they’re (inadvertently?) brewing.

So, as the world’s nations and supragovernmental and intragovernmental organizations watch the storm building on the seas and the great fish circling down below, we ought to at least remember one thing: No one, whether individual or society, gets to run from Nineveh. They tried in the 1930s, but they didn’t get very far. When the whale rises, it only ever ends in one of two ways: deliverance or death.

Anthony Doyle is the author of four books: Jonah’s Map of the Whale and Other Poems (Old Scratch Press, 2025); the novel Hibernaculum (Out of This World Press, 2023); and two children’s books in Portuguese, O Lago Secou (Companhia das Letrinhas, 2013) and O Livro de Sereias Surpreendentes (Grua, 2015).